On a high rocky headland in the corner of one of Newcastle’s most popular and well known parks, lies the slowly crumbling remains of one small part of Australia’s WWII coastal radar defence system – the Shepherds Hill Radar station.

At the end of the 1930s, radar was advanced cutting edge technology whose development was of more academic than practical interest. WWII changed all that. The British quickly surrounded their country with a chain of radar stations and Australia did the same. Many credit the development of radar with finally helping the allies win the war.

With Remembrance Day last week, we got to contemplating this vital part of the national defence, and the men and women who developed and staffed it. Those who served at home are sometimes – if not forgotten, then at least not as well known.

There are many amazing things about the story of Australia’s WWII radar defences. For one thing, the speed with which it was rolled out. At a top secret meeting just before war was declared in 1939, the Brittish decided to share their technical knowledge of radar with allied countries like Australia, South Africa and Canada.

A radiophysics lab was set up at Sydney University to work on developing the new technology for defence purposes and the plan was a chain radar stations around the coastline. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour in December 1941 and continued their march south through Asia, things really got cracking. By 1945 there were 142 ground based radar stations around Australia, and 355 across the south west Pacific.

Australian scientists went on to create the Australian Air Warning radar – a significant advance on the cumbersome designs which had initially come out of Britain. Among other things, the Aussie design did away with large cumbersome towers and replaced them with a lightweight and robust aerial. The units were manufactured by the Gramophone Company of Homebush in Sydney and were used throughout the Pacific on both land and sea.

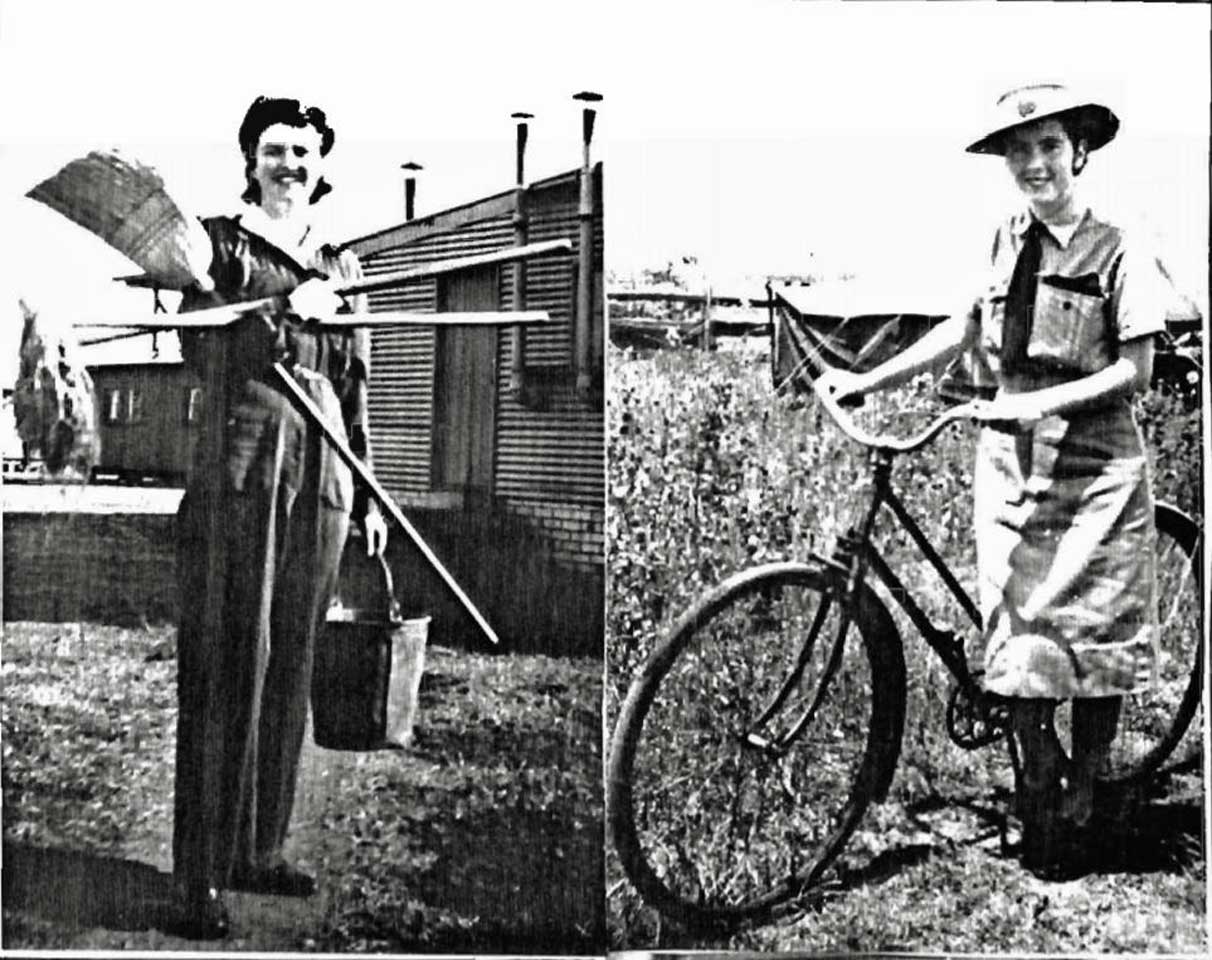

Another interesting thing about this story was the major roll women played in staffing many of these radar stations. With so many men away fighting overseas, it was women who were trained to scan the skies and seas for possible enemy attack.

The men and women who set up and operated these stations played a vital role in defending Australia. The radar stations themselves were frequently in remote and challenging locations. Conditions for the operators were basic at best and the work itself could be extremely monotonous – hour after hour of scanning and plotting and recording.

What we saw

Old radar stations can no doubt be found in many places in Australia, but we set off to look at some of the radar history close to our home base on the NSW Central Coast. This exploration took us from the heart of Newcastle, to the swamps and wetlands of Hexam and then back down to the rugged bushland of Bouddi National Park on the Central Coast east of Gosford.

Shepherds Hill

The south Eastern corner of Newcastle’s King Edward Park was the first stop on our radar mission. This spot known as Shepherds Hill – has been a fort since the 1890s. With its commanding views up and down the coast – it was the ideal place for a fort. At the front of the site there is an observation post – and it was on top of that that Australia’s first RAAF experimental radar equipment was installed.

The trial radar was installed in January 1942. Then, six months after war broke out in the Pacific (June 7 1942) a Japanese subamrine shelled Newcastle. Nobody was hurt and it did minimal damage – but it was a wake up call. At that time, Newcastle had huge coal and steel output which made it strategfically important to the war effort. During the course of the war key defence inudstries would be established in the city – armoured vehicles, ammunition. It all needed to be protected from enemy attack.

The RAAF set up three additional radar stations in the area – One at Tomaree at Port Stephens in April 1942, another at Ash Island near Hexam in August, 1942, and a third at Mine Camp near Catherine Hill Bay in February 1943.

The Shepherds Hill experiemental equipment was dismantled and was installed as number 19 radar station at Bombi on the NSW Central coast in April 1942 – where it would protect the northern approaches to Sydney.

Ash island

RAAF radar stations were known by numbers – and Ash Island was known as 131 Radar. It’s about 20 minutes drive from Shepherds Hill, within what is now Hunter Wetlands National Park. The turn off to the Kooragang wetlands and Ash Island is by a narrow bridge off the Pacific Highway, across an arm of the Hunter River (just across the road from Macca’s). A number of sealed and dirt roads criss-cross the park It’s right at the end of Milham Rd just passed the “city farm”.

You can wander in and around the buildings, read some information signs and contemplate how harsh and remote the spot must have been in the 1940s. The site is used as a wetland education centre these days and on the day I was there one building was open so we got to take a peek inside.

An excellent account of the operation of this 131 Radar and recollections of its personnel was produced by Morrie Fenton in 1995. Well worth a read:

“131 was fairly typical of the small RAAF stations on watch along the east coast of Australia, set up quickly when the threat of enemy action was greatest.”

The station watched over Newcastle for several years and its equipment was upgraded several times. The all-male crew soon became almost entirely Women’s Auxiliary Australian Air Force (WAAAF) personnel.

Radar operator Helen Mann recalled her experience there in Morrie Fenton’s research:

“After some weeks the order came to relocate to Ash Island and we had visions of sandy beaches and palm trees. We left on 7th August, my 19th birthday. It was somewhat disenchanting to drive across the bridge at Hexam and discover mud and mangroves inhabited by huge striped spiders and swarms of crabs whose burrows were exposed at low tide. And we mustn’t forget the mosquitoes – huge Hexam greys and vicious little black ones. At first we were accommodated in tents while the cookhouse, with minimum weather protection of corrugated iron sheets, was HG for our cooks Ernie Allen and Bertie Britain and their cat Lousy. Carrying a plate of food from the cookhouse to the mess tent on a windy day was likely to result in the food being blown off the plate, but if there was no wind, the blowflies were an even worse hazard.”

The buildings consisted of two “almost impregnable” concrete igloo operations rooms. Apparently these were of English design and were intended to be underground – but at Ash Island they sit above ground. The footings of the radio antenna still remain as well. The camp for the station’s 50 or so staff was about a kilometre away and included sleeping quarters, a kitchen and mess and an assortment of other buildings. Nothing obvious remains of these. First hand accounts of life there describe many hardships – but also a sense of purpose and camaraderie as people went about their work.

Number 19 at Bombi

When the Shepherds Hill radar was dismantled in 1942, it was quickly reassembled at a remote high spot between Macmasters Beach and Killcare. Almost nothing remains of this station save the written records of it’s existence, and the slowly disappearing remains of a sandbagged machine gun post which once guarded the perimeter of the station. You would easily walk past it if you didn’t know where to look.

To reach the site, take The Scenic Rd between Macmasters Beach and Killcare, looking for a left hand turnoff into Bouddi National Park via Mt Bouddi Rd. The turn is hard to see and is almost directly after Bombi Road South. Follow the road to the end where there is a car park, picnic area and toilet. The unmarked trail goes off to the left as you enter the car park.

The station’s purpose was to monitor enemy air and sea movements on the northern approaches to Sydney and was supposed to have been absolutely “top secret”. Accounts from the time suggest it might in fact have been the worst kept secret in the district with local children used to run errands between lookout positions and the main radar station.

A winding dirt track from Gosford brought in supplies, and when not involved in the tedious procedures of plotting planes and ships, the staff would swim at local beaches and hold occasional film nights and the like. In October 1944, bushfires threatened to burn down the camp.

At it’s peak, 23 men and 18 women staffed the station which started out in tents but eventually moved into more permanent buildings. No photographic evidence of the station could be found, but the mess hall and a generator shed survived into the 1980s but are now long since gone. A private home now occupies the site and only the machine gun post within the national park is accessible.

RAAF Historical Officer Robert Piper contributed an article to the Central Coast Express in 1982 about the station. Here’s a little exerpt:

“Stations were usually quite small and in isolated areas. Their staff consisted of a handful of men and women under a junior officer. Water supplies were nearly always a problem with food and equipment and mail being delayed by poor roads.”

“Though fully occupied during working hours, when off duty men and women found life on a radar station monotonous and lonely. They had to organise their own activities and entertainments. The units ran concerts, talks, quiz sessions and planted vegetable gardens. Sports meetings, footbal and swimming helped to keep them fit and reasonably contented.”

By the end of 1945, the majority of Bombi staff had been reassigned and in January 1947 the unit was disbanded and dismantled.

Want to know more?

See our video of this trip over on Two Minute Postcards’ Facebook page

Read more about the history of radar in Australia during WWII